HERE’S HOW TO DO IT.

Greenwashing: How to expose it

Greenwashing is one of the major threats to combating climate change. From some of the world’s biggest companies to small businesses, millions of commercial actors strive to paint themselves green without having earned the right to do so.

By Kristian Elster and Mahima Jain

As consumers are becoming more concerned about climate and environmental issues, the use of greenwashing is increasing.

The tools used by greenwashers are manifold. In this article we will look at different kinds of greenwashing and how to uncover them in a constructive way. We will also look into how to cover climate start-ups.

Carbon credits

Many companies seek to offset their CO2 emissions by buying carbon credits, instead of actually cutting emissions. The theory is that they pay someone else to cut emissions on their behalf. Airline companies are an example. They typically offer customers to buy carbon credits to offset the emissions from travelling. In practice, the trade in carbon credits have been shown not to work in many instances. Some emissions cuts have not been real and others have been counted twice. A EU study concluded that 85 percent of the projects it examined were unlikely to achieve their reduction claims. Wayback Machine (archive.org) Last year, an investigation by The Guardian revealed than more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless. What’s more: the international political discussions to give it a regulatory framework are at an early stage, with multiple gray areas still to be resolved. Covering this topic does not mean considering that “carbon credits are bad”, but it does mean that a) they need tracking from our part to see how transparent they are and b) they need an analysis as to whether they are being a complement to the necessary climate action or a way to continue with business as usual. The Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) has a good reporters’ guide to investigating Carbon offsets. Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Carbon Offsets – Global Investigative Journalism Network (gijn.org

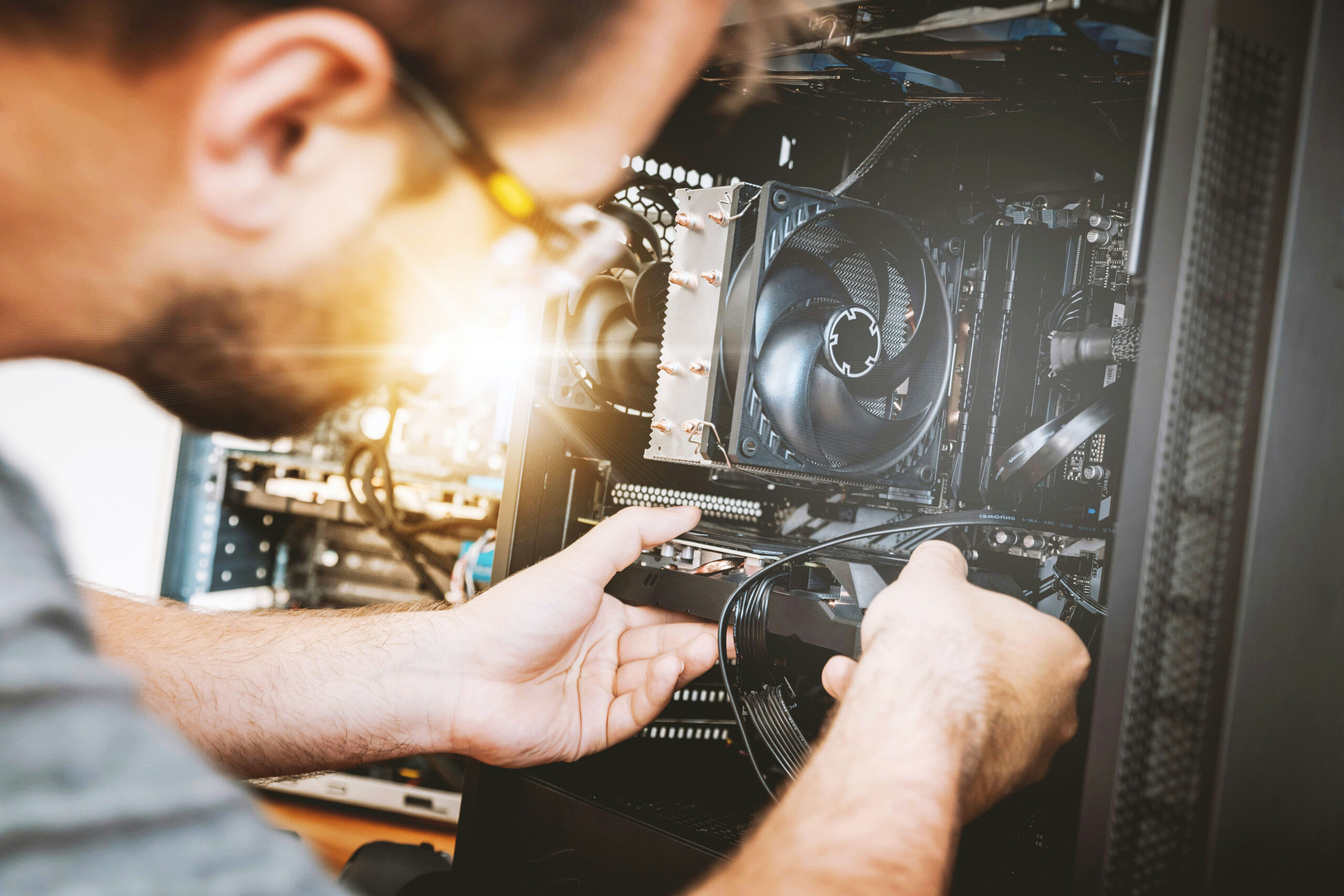

Repairing items

One way to check if a product is sustainable in its life cycle is to see if it’s possible to repair when broken. According to the E throwing away goods that could be repaired leads to 35 million tons of unnecessary waste annually in the union. Furthermore, this does not contribute to climate action because, when discarded, there is an inefficiency of all the resources that were used throughout its useful life. The EU is working on introducing a “right to repair” for a wide array of products. In Latin America, independent initiatives like Club de Reparadores offers citizens an alternative to repair products collectively, even sometimes in partnership with big companies. They could be a good reason of a story to show the issue, what’s necessary, what’s possible.

Name changes

Recently, some of the world’s biggest carbon emitters, such as conventional energy companies, have attempted to rebrand themselves as champions of the environment. For example, the Norwegian state oil company Statoil in 2018 changed their name to Equinor. The idea was that the name should reflect that “the company was about more than oil and gas”. However, by 2024 more than 99 percent of Equinor’s energy production comes from oil and gas. This is part of a larger change that has occurred in recent decades. Even though they knew about the contribution of their activities to climate change, in the 1980s and 1990s the most responsible companies did not contemplate climate action in their policies. In recent years the situation has changed. Today they say they are interested in the issue, they announce carbon neutrality goals, but how real are these commitments? Journalism here has the enormous challenge of tracking the transparency of these promises and delving into the actions they are truly taking, or not, and the ones they need to take with urgency, ambition and justice. In this regard, Global Witness carries out in-depth investigations into the greenwashing behind the climate commitments of fossil fuel companies.

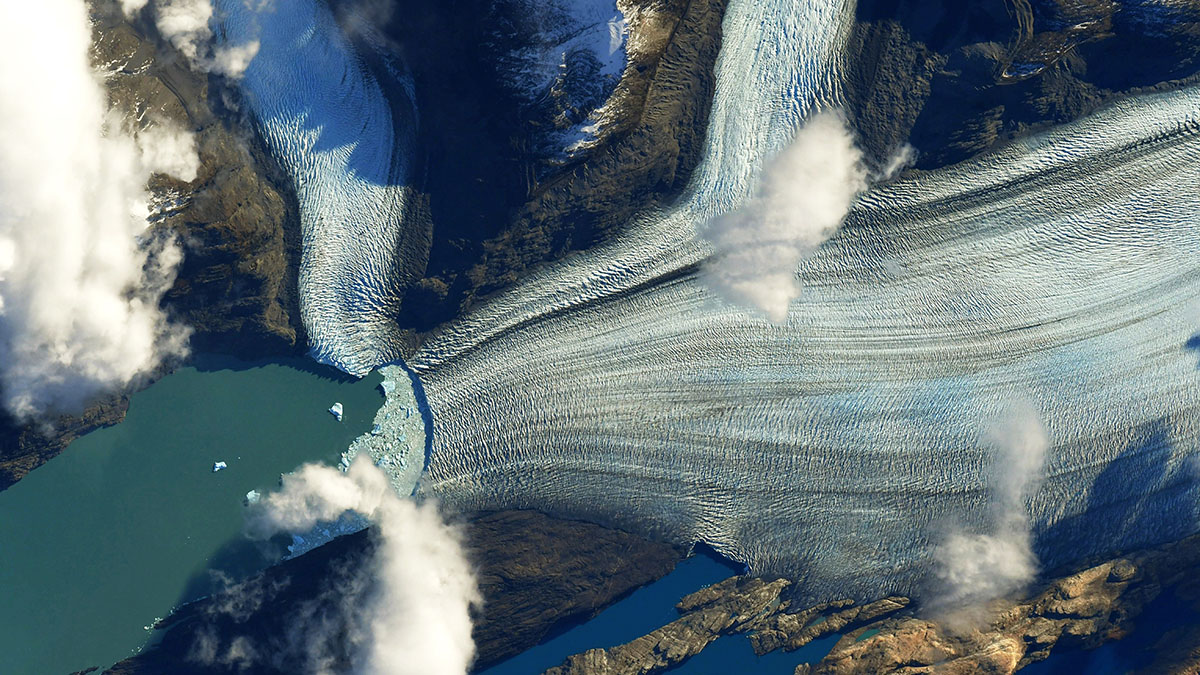

Green grabbing

Green grabbing is a term for grabbing land or resources for environmental purposes. This can result in local residents’ displacement from land where they live or make their livelihoods. The concept of green grabbing was first used by John Tidal in an article in The Guardian in 2008. The reasons for grabbing land might ostensibly be good. Examples can be for areas planting trees for carbon emissions trading, areas for renewable energies or simply for conservation effort. The victims of green grabbing will tend to be societies weakest, while the perpetrators might be government actors, NGOs or others with a good reputation.

Technological solutions

Carbon capture and storage, or carbon capture, storage and/or use are technological solutions where the excess carbon is sucked out of the atmosphere, stored or reused. However, they are not the easiest solutions: they are expensive, difficult to be implemented on scale and scientists have been working to improve themfor decades. Companies may use, promote or promise these technologies for greenwashing. Instead of changing their carbon-intensive processes, they may use this as an excuse to continue business-as-usual. When covering carbon capture-related developments it is important for journalists to understand the technology readiness level of the solution offered. Is it scalable? Is the company that plans to use it also making its process less carbon-intensive while implementing this solution? Does it require a lot of energy? Where does that energy come from? What are they going to do with the carbon captured? These are just some critical questions journalists can ask when writing about potential technological fixes for the climate problem. Remember: there is no single solution to act on climate, science has evidenced that carbon capture will be one complementary technology to be used, but the reduction of emissions is the key action to change the curse of the problem. Here are some useful resources for the next time you work on a story about this: What carbon capture and storage is, by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) 7 things to know about carbon capture, utilization and sequestration, by World Resources Institute Informative guide on carbon capture, utilisation and storage, by International Energy Agency

Start ups

Covering start-ups in the climate sector can be engaging journalism. Though it is far from the solve-all-solution, the world will need new technologies being put into practice to handle climate change. Start-up companies are by definition positive. It’s therefore important to check their numbers and put them in perspective. A good example comes is a Reuters story from 2021 about Climeworks AC in Iceland. The article explains the technology and why there might be a case for it in the future. But it also put the numbers in perspective. The plant in Iceland will remove 4000 tons of CO2 per year. Reuters has made the calculation that’s the equivalent of the annual emissions from about 790 cars. Put another way, since the world emitted about 31,5 billions tons of CO2 in 2021, there would be a need for almost 8.000.000 plants like the one in Iceland to neutralize it.

Menu