The Constructive Institute offers an annual fellowship program to around 10 media professionals to spend an academic year at the Constructive Institute in Aarhus, Denmark. The fellows are expected to return to their newsrooms to share their insights with their colleagues and implement constructive reporting into their daily work.

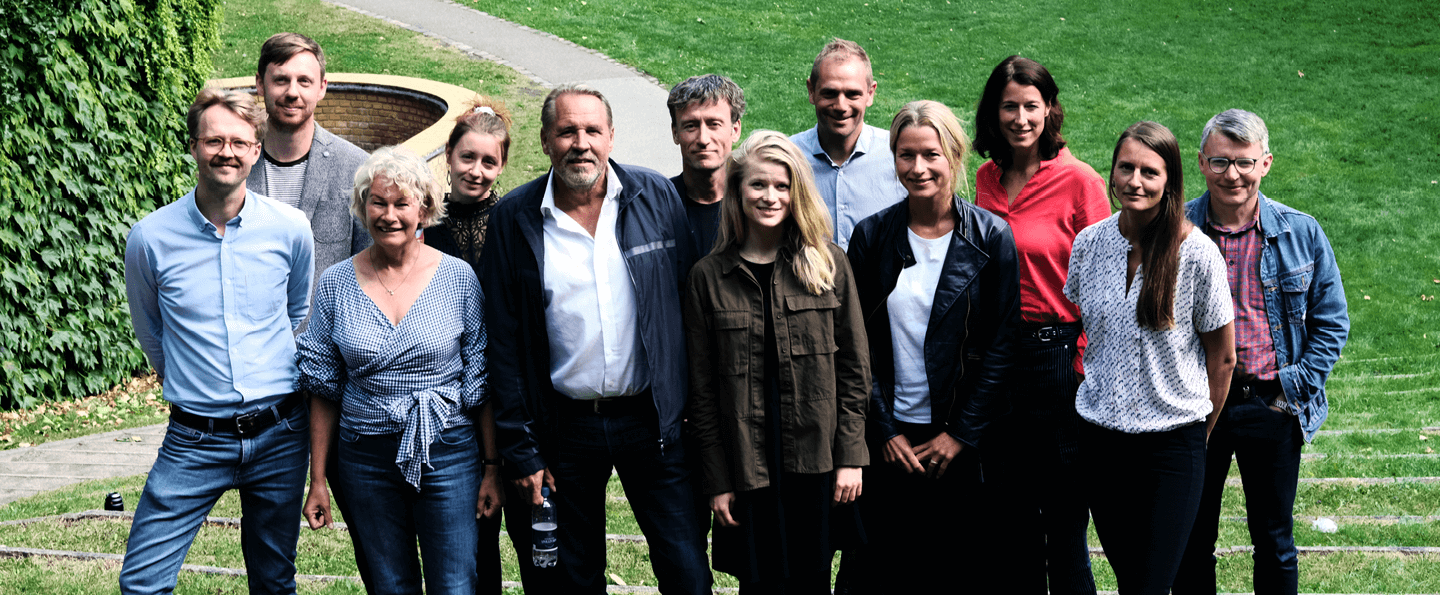

We are proud to present to you the talented constructive journalism fellows of 2024-2025.

Being There

An essay by Thomas Stokholm, Fellow at the Constructive Institute 2024/2025

In the 1979 film Being There, Oscar-nominated actor Peter Sellers plays the role

of Chance the Gardener, a middle-aged, simple-minded man who has spent his

entire life tending the garden of a wealthy, aging man. Other than gardening, all

of Chance’s knowledge comes from watching television.

When the old man dies, Chance is abruptly cast out of his secluded security.

Through a series of improbable encounters, he ends up in the home of yet

another wealthy, dying man—an advisor to the President of the United States.

Misunderstood due to his plain and literal way of speaking, Chance is mistaken

for a brilliant mind. He eventually almost becomes a trusted advisor to the

President—completely unaware of the world around him.

In one of the film’s most iconic scenes, the President asks Chance for advice on

how to stimulate national growth. Chance replies:

“In the garden, growth has its seasons. First comes spring and summer, but then

we have fall and winter. And then we get spring and summer again.”

The President receives this painfully obvious truth as a deeply wise and insightful

statement.

Being There reminds us that if you look the part, sound right, and speak in

platitudes, you can get quite far in life.

—

As part of the 2024/2025 fellowship, I was here at the Constructive Institute, I’ve

had the privilege of meeting many brilliant, committed journalists. One of them

will even be my close friend for life. We are all articulate, confident, and come

well-equipped with bulletproof solutions to the world’s problems. We know how to

solve the climate crisis, eliminate biases, and fix representation—whether it’s on

a board of directors, a dying legacy newsroom, or the cast of a reality show.

Most of all, we believe we can fix the crisis in journalism. Our ambition is to help

shape the news of tomorrow. Our mantra is to report with nuance, focus on

solutions, and promote democratic conversations to pursue the best obtainable

version of the truth.

We have the answers. We will go far.

While Chance the Gardener walks into the world to share his wisdom, we fellows

enter a closed space of reflection in the lounge—then visiting endangered

newsrooms, meeting inspiring journalists, and exploring radically new models of

journalism. We actively seek professionals and ideas that reinforce our mission.

And it is, without exaggeration, a mind-blowing experience—one that I believe

every journalist should have at least once.

Talking journalism with journalists sharpens your thinking. You begin to see

possibilities – or pitfalls. If I were to borrow and slightly twist Chance’s famous

words, it might go something like this:

“In the world of news, sensationalism and negativity bias have their seasons.

First come focus on polarization, distrust, and half-truths. Then come focus on

news fatigue and broken business models. And then we get back focusing on

sensationalism and negativity bias again.”

I am far too seasoned in documentary and news work to doubt the value of

constructive journalism. But I remain cynical or perhaps even naïve enough to

challenge the prevailing mindset of my profession.

What if we stopped acting like journalists?

When critical scrutiny becomes a default position, it can produce a kind of

reflexive negativity. Not because the facts require it, but because it feels safer.

Because it seems more objective. Because it’s what we were taught is

“journalistic.”

What if we stopped acting like journalists and instead just were journalist?

We act as though stories only exist when we apply criticism—so we remain

locked in negativity bias. But what if we allowed ourselves to be curious, even

enthusiastic? To see opportunity, not just opposition?

We behave as if the world is constantly trying to deceive us. But most people are

okay. They have hope. They have dreams. Should we really hold them

accountable for that?

We often chase “truths” that few people are genuinely interested in. Maybe we

should instead seek realities people actually care about. People would rather be

invited into agency, encouraged to take control of their lives, than have

journalists assume that role for them.

What if we cared more about people’s lives, and then demanded accountability

from those in power—in that exact order?

People outside journalism tell stories that move people. Journalists tell systems.

And too often, we leave the people behind.

This isn’t doctrine. Just a constructive slice of advice.

In the final scene of Being There, Chance walks on water—an ambiguous ending

that hints at divine symbolism. But let’s take a more grounded interpretation: that

it’s his naive purity that allows him to keep on walking.

Perhaps, as journalists, we too could be naive. Naive, caring—and critical.

A Year with Room to Think

Over the past ten months, I’ve had the lid lifted off my brain and new oxygen added

to my professional and creative thought processes. It’s been an intellectual recess,

where new ideas have had space to flow freely.

I wish every journalist could have a year like this. A safe space where you can doubt,

think, and talk about the role of journalism in an increasingly complex world. Where

you can dive into the hyper-local — and at the same time lift your gaze from the

computer, view journalism in a larger context, and remember why you once chose

the profession.

Returning to my old student city of Aarhus has been a particular joy. I didn’t study at

the university, but at the Danish School of Media and Journalism — and being back

has felt both grounding and energising. Aarhus has grown and become a bigger city,

but it still exudes life, warmth, and a down-to-earth vibe. There’s always something

happening, especially on the cultural scene — from exhibitions and talks to

concerts and cafés full of conversation.

I’ve especially appreciated the opportunity to follow courses at the world’s most

beautiful Aarhus University. It’s a pleasure to bike or walk through the university

park on the way to class. The changing seasons transform the old oak trees from

green to golden to bare.

The courses in Equality and Democracy at Political Science and Health Inequality at

Public Health Science made an impact, not just academically, but personally. The

instructors made it clear we were welcome. They engaged us, asked questions, and

invited us into dialogue. I was also given the chance to present my journalism

project to students at Public Health – it was both fun and motivating to stand in

front of future healthcare workers in the regions and municipalities and give them

insight into the realities we journalists encounter.

If you want to, you can also attend courses at the Open University. It became a

tradition for some of us fellows to take a course together and then hold a “food

club” in the mathematics cafeteria.

The study trips were powerful in different ways. We visited newsrooms across

Denmark and heard how they work – and survive. It made a strong impression to

meet media leaders working to make journalism so relevant that readers and users

are willing to pay for it.

We also went abroad.

Kenya made an indelible impression: courageous media leaders, complex political

realities, and a sense that we as journalists must broaden our gaze and not only

focus on the Western world. Africa isn’t “the overlooked continent.” It’s just us who

overlook it.

The USA left me overwhelmed. The country that once gave me a sense of freedom

now feels constrained. The people we met at KQED, Substack, Stanford, Berkeley,

and CitySide were honest, and their stories of division, hopelessness, and lack of

resistance were disheartening.

One of the best parts of the year has been the atmosphere in the lounge: morning

coffee, small talk, visits from children and dogs. The human and the informal — and

not least the morning song every day. That’s what makes you want to come back the

next day.

I’m grateful for the past ten months. For the freedom, the academic depth, the

fellowship, and the shared time with others. For all the questions still echoing in my

mind — and hopefully continuing to do so.

If you’re considering applying for a fellowship, do it. If you’re already accepted: use

the year — and use each other. It’s a giant gift shop full of free offerings, ready to be

picked off the shelf and used to enrich yourself.

Eva Højrup, sundhedsreporter, TV2 ØST, juni 2025

Maturing a recently hatched journalist

I have now completed my fellowship at the Constructive Institute.

It has been quite different from what I expected. However, I know that I have become a much better journalist than when I started.

Why? Well, for several reasons.

The first reason is time. I have had time away from the sweat-inducing deadlines at work and I have had time to think. What is the purpose of what I’m doing, and what do I want the recipients of my publications to achieve and learn? I have not had time to reflect on this properly, since… ever. But now I finally had the time to.

The second reason is that it has not been that many years since I completed my bachelor’s degree in journalism. The last ten months I have been sitting amongst brainiac experienced fellows the entire time. They know the industry far better than I do and have a whole world of experience. Dear Lord, I have learned a lot from my fellow fellows, and dear Lord, are they capable of initiating a discussion from anything.

The third reason is that I was able to choose the courses that I found most interesting from the ENTIRE Aarhus University course catalogue. Thus, I entered as a kind of undercover student (19-year-old Nanna would have regarded it uncool, but 29-year-old Nanna loved it). I have learned things from political science, anthropology and creative communication that I can use in so many aspects of future jobs.

I rediscovered my own joy in writing different journalistic genres, I learned about early days of democracy, and I have learned about the many zealots who are trying to preserve peace on earth.

But it hasn’t all been easy and cushy. It has been a difficult decision regarding whether a smart team with a great deal of knowledge about world affairs and environmental issues should travel several thousand of kilometers by plane for study trips. This concern divided our team in two for a while and made it impossible to make a joint decision, until we all finally agreed to go. We certainly learned a lot from the two study trips to Kenya and the US, and I certainly wouldn’t have been without these trips. But just like in journalism, it’s perhaps time for this wonderful fellowship to reflect upon this matter as well.

Even though I felt amazing for many months, it hasn’t been easy being away from regular work for ten months. Now that I’m getting back to work, I almost feel like I must start over in catching up. There are so many systems and so much development that I haven’t been able to follow, since I work with social media where trends and platform development move faster than the speed of light.

With that said, it also turned out that it was in fact necessary for me to start from scratch regarding journalism. It has been necessary for me to wipe out almost everything I have been taught during my internship and various full-time jobs. Or at least forget about rules within journalism, widely agreed upon amongst lecturers and workplaces.

I have learned that journalism does not have to be black or white. That a news story requires time and proper reflections, rather than being written and published quickly. That continuous reflections on what I am doing and for whom I am producing for is the most important. And I have realized how significant the role of a journalist is – especially in this ambiguous world.

I would like to sincerely thank Tryg Fonden and Constructive Institute for this wonderful

opportunity to develop both myself as a journalist and our journalistic take on social media news at Danish TV 2 Regions.

Reflection essay

June 2, 2025

Alright. I’m dividing this essay into two parts. A tentatively constructive part for those of you wondering whether to apply for a Fellowship. And a second part for those of you curious to know what message I wrote to myself on the very first page of the notebook I carried with me for ten months.

Part 1

I applied for a Fellowship in the hope of finding my way back to journalism. The recent years’ obsession with page views, conversions, and all sorts of other noise instead of actual journalism had taken a toll on me. I had lost sight of the big “why.”

Despite my small, protected part of Jyllands-Posten, where I — unlike many other places in the industry — have been supported in writing about people and societal undercurrents rather than systems, my thinking had grown sluggish.

My journalism had become inward-looking and slow — and I can barely bring myself to type this journalistic cardinal sin, but at times even navel-gazing. I had begun shelving important topics out of fear they wouldn’t generate clicks, and I obsessively tweaked headlines if my latest piece didn’t make it to the top ten most-clicked list.

In my 20 years in journalism, I’ve often worked as an agent of change — both as a leader and as a reporter — but suddenly, a new side of me emerged. A resistant side.

It hit me when a colleague sent me a photo of myself. He had taken it secretly during a workshop led by a bizarrely enthusiastic editor, who was pushing ideation left and right — despite, like me – clearly having lost their journalistic compass. In the photo, I’m sitting with both knees pressed up against the edge of the table. My face is turned downward, eyes locked on a crocheted dishcloth in turquoise yarn, which I’m tearing at with a crochet hook. My colleagues called them Alvi’s rage cloths. I channeled all my frustration — with the maddening click-fixation, with Putin, with Trump, with everyone who breathed in an annoying way near me — into hopelessly crocheted cloths. They were wonky and misshapen, but I wrapped them nicely and sent them to select colleagues along with home-written satirical poems about the state of the world, always ending with: “Let’s have a glass of wine — but not a toast for Putin, that stupid swine.”

It was neither flattering nor constructive. I admit that, though I’m tempted to add some mitigating shades to the story. Because it’s also about death and grief. About friends being laid off in ways that cut deep.

And about suddenly not being able to press the gas pedal in your car, because the connection between your brain and the right side of your body no longer wants to cooperate.

Luckily, it’s also a story about deciding to pull your kids out of school and travel the world as a family for half a year. To lie on the roof of a riverboat counting flying foxes in the fading twilight, turning your face toward your son and thinking: I only have now. We shouldn’t squander our working lives if we can help it. And I sure as hell didn’t come here to write for clicks or to throw more fuel on the smoldering fire of polarization that terrifies me and has, for years, led me to play a mental game I call: What do I pack, and who do I team up with when the zombies come?

That’s what I wrote to Ulrik Haagerup. Not in those exact words, but close. I wasn’t wearing a t-shirt that said “Constructive Journalism Rocks” when I walked into the interview with Ulrik Haagerup and Orla Borg — and I’m not wearing one now. But I carry ten months of conversations about what journalism, in service of society and its citizens, can and should contain. I’ve been offered inspiration and insights from Denmark and abroad to build my “why” and my “how.”

Some of my articles would likely not be accepted by an algorithm designed to measure constructive content, such as the one Constructive Institute is developing with the help of AI and language researchers. That’s because I hesitate when it comes to incorporating the third pillar of the constructive framework — “tested solutions that can be scaled” — into my work. Still, I believe I work “aspirationally constructively.” By diving into societal currents and attempting to broaden public conversation by elevating people and perspectives, and using storytelling to invite more people in.

But the “solutions” pillar… yeah… it still sits awkwardly with me. When is a solution a real solution? And can I — with my limited subject-matter expertise — really assess whether my sources are right about Carbon Capture and Storage, or just gaslighting me with optimism?

Even after three weekly sessions in the constructive lounge, where staff, media guests, and researchers from all over have sparked discussions, I remain uncertain.

For example, I’m calling for a proper reckoning within the constructive world with the notion of so-called “aspirational objectivity.” It’s still often presented in the lounge as a natural norm among Danish journalists — but after ten months of reading sociological research on implicit bias and societal masterplots, I’m even more critical.

We should strive for objectivity in our journalism, while knowing it’s ultimately unattainable and that we are biased by nature. The blind spots that follow can mean that journalists shy away from challenging shared, unspoken norms in society — out of fear of being cast out. It can mean that we all chase the same agenda.

Or that media end up spotlighting the same voices and speaking to their own, without realizing they’ve alienated a silent, disconnected majority.

To truly aspire to objectivity requires a consciously acquired awareness, a systematic method, and psychological safety in the newsroom — so blind spots can be challenged. And the fastest route there? Collaboration with people who aren’t like us — in age, gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, education, upbringing, body, or soul. That can shake the inherited cultural lenses and break us free from journalism dictated by the masterplot of our time.

And activist journalism? Just a few months ago, I would have recoiled at the word — one of the big taboos in media circles. Activism in journalism is a dangerous road. On that, the constructive fathers and I agree. But the lounge conversations have shifted something in me. If I follow the line of thought that all journalism is unconsciously value-based, then parts of our journalism may already be unconsciously activist. And if that’s true, then maybe the time has come to own up to our value-based journalism. We can work actively to ensure we’re not operating with conscious or unconscious goals baked into our reporting. Or we can be open about our bias and our value-laden starting point — and bury the idea that we “just tell people what’s going on in the world.”

I love the BBC’s campaign slogan “Made to Make You Think” — but I’ve allowed myself to take it further: “This is my standpoint in the world. I want to make you think — but I won’t tell you what to think.”

I carry the best of my ten months as a Fellow forward — along with a conviction that I’ve lived up to Ulrik Haagerup’s advice at the start of the semester: “This year is yours. Just promise me one thing. Be curious.”

A Fellowship at Constructive Institute becomes what you make of it. You’ll be given freedom — but use it wisely, because time disappears quickly among study tours, two academic courses per semester, reading groups, lounge talks, workshops, and projects. You’ll make new friends while surrounded by students eager to explore and understand the world. You’ll start reading again — and suddenly see more layers in reality and begin to notice dynamics instead of isolated incidents. You’ll meet Fellows from Stanford who will confront your journalistic privilege blindness. Instead of chasing the ball like a chaotic pack of little leaguers, you begin to find your position on the field.

In journalism it seems that we often push people with opinions rather than people with knowledge. But in encountering sociology and conflict research, I found that the moment my thoughts begin to drag, when it gets heavy and I feel like reaching for my phone because thinking and understanding is hard… right there, someone with expertise and facts has paved the path so I can follow it.

My most important takeaway? I want to keep reading. It sounds banal, but it’s not — because it has cleared a staggering amount of gunk from my lenses.

My insights about structural challenges and bias — in society, journalism, and the media world — are something I’ll be working with in the years to come. But first, I’ve been inspired by encounters with media professionals who are finding new ways to foster dialogue and serve their audiences. I’ll activate those insights when I return to my workplace this fall in a completely new role.

Part 2

Head of Institute Orla Borg has a rule: No phones or laptops in the lounge. You write by hand. In a notebook.

It turned out to be a constructive exercise in itself — and it means some of my notes are now nearly illegible. But on the very first page, in large letters, I wrote: “Big ears – small mouth!”

A reminder to take in before sending out.

How did it go? Let’s talk about it over a coffee at The Royal Library. You’re always welcome to reach out: jamillasophie@gmail.com

A Curiosity Year in Aarhus

Back in May 2018, a political party proposed that everyone should be entitled to a curiosity year for every ten years spent in the workforce. A full year on paid leave to explore new knowledge, reflect on the future, and grow a little wiser. That spring, many of us political journalists at Christiansborg had a good laugh at that. The proposal struck us as entirely unrealistic. Utopian even.

Fast forward to June 2025, and I find myself immersed in that very utopia, deep into my own curiosity year. No deadlines. No stress. Far removed from looming rounds of layoffs. At the Constructive Institute in Aarhus. Nestled in the soft furniture of “the lounge,” as they call it, where top-shelf guest speakers drop by in numbers: media professionals, researchers, politicians, entrepreneurs, and others with something important to say. And where we have time to exchange views and discuss the current state and the future of journalism. What a privilege.

Alongside that, we have had close to free rein to explore courses at Aarhus University. I’ve taken political science classes on democracy and inequality, studied personality types in psychology, and delved into social and political philosophy. It has given me new perspectives on my journalistic beat as a political journalist and academic knowledge on broader topics. Nice.

There were also study trips. To Kenya, with a focus on journalism, entrepreneurship, and climate. And to San Francisco, where media bosses, journalists, university professors, and tech professionals still seemed to be in a state of shock after Donald Trump’s recent return to the presidency. Timely and rewarding study tours, to say the least.

All those good things considered, the very best part of the fellowship was something else: The other fellows. Ten months of intense interaction with ten colleagues in a sort of folk high school environment, and you get to know each other pretty well. Both professionally and personally. What drives the others. How things are going at their jobs and in their family life. Their recurring themes and obsessions and the signature questions they pose to every speaker. Their values and backgrounds, their professional opinions and their quirky idiosyncrasies. What annoys or excites them, their favorite wine and music, what they’re unsure of, and what they’re absolutely certain about.

They came from many corners of the profession: regional and local media, live journalism on stage, health reporters, a SoMe editor, two authors, one from Finland, political reporters covering city councils and Parliament, educators, freelancers, feature writers, podcast producers. At the end they felt like family.

Of course, a stay at the Constructive Institute isn’t just living the utopia. There were frustrations. A project that was hard to write, sessions that could have been structured better.

At times, it was difficult to grasp exactly what we were learning, what the deeper meaning was, and how it all fit together. There were occasional moments of friction. But I count these obstacles as minor details in the big picture.

What remains is having spent ten months reflecting, learning, and thinking together with kind, curious, and smart people in an inspiring environment. In time, I’ll probably be able to articulate more precisely what I’ve taken with me, and how it will shape my life and work in the years to come. For now, I’m just grateful to have been lucky enough to do what once seemed more or less unthinkable for a political journalist: to have a whole Curiosity Year.

Random reflections from a departing fellow’s notebook

(take what you can use and leave the rest)

What a privilege

As a lecturer at Danmarks Medie- og Journalisthøjskole (DMJX), I don’t have constant deadlines that the fellowship can free me from for ten months. So, for me, deadline-free time hasn’t been the greatest gift. No, without a doubt, it’s been: 1) My fellow fellows, of course. Wow, what a privilege to be part of such a wonderful group of people. And the best part? I’m happy to know I’ll still be part of this community even after the fellowship ends. 2) Access to the university’s course catalog — omg. My courses on conflict narratives, framing, democracy, and polarization made my brain spark with new insights and gave me a wealth of ideas to bring back to DMJX. I wish I could keep that access forever. Can I?

Trust: let’s remember the nuances

At DMJX, we aim to teach our journalism students to be nuanced and to always keep their critical thinking switched on. In fact, if I had to boil it down, I’d say that’s one of the most important things to take from the first part of journalism school. Luckily, that aligns perfectly with Constructive Institute’s second pillar. Overall, we are teaching journalism in a way that resonates with the broader thinking around constructive journalism.

But I just want to offer a reminder: when we talk about the need for constructive journalism, it’s often framed as the solution to a number of problems: news avoidance, polarization (“the new pandemic”), and a “trust meltdown” among the recurring ones. Yes, all three are important issues to address, but let’s not forget the nuances. Take trust as an example: Yes, there is distrust in the media in many parts of the world, with the U.S. as a prime example. But Denmark is consistently highlighted as one of the countries with the highest levels of media trust — and it’s even stable over time (Andersen et al., 2021). Most recently, in the new Digital News Report from Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism , which is often used as a springboard for constructive journalism, Denmark’s relatively high numbers stand out – again. I also noticed that, according to the report, overall trust in the news has remained stable for the third year in a row. And as postdoc Miriam Kroman Brems recently put it, Denmark is “a least likely case” for distrust — and that’s also the title of her PhD dissertation: Alternative news use in a high-trust media and political context. “High-trust media context.” Wow, aren’t we lucky? What if that was part of the narrative about journalism? Sounds pretty constructive to me.

You can’t be what you can’t see

Each fellow has, in their own way, taught me something — which would be far too boring for any reader if I tried to list it all. But take Alexandra Wake from RMIT, Australia, for example. Like me, she teaches journalism — and their staff is genuinely diverse: race, gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and (dis)ability. As she said: “You can’t be what you can’t see.” I’m taking that one home with me and bringing it up with my colleagues. Imagine if we hired differently — so we represented the population just a little bit more…

A snow globe brain

We’ve met at least three times a week in the lounge at the institute, often with outside guests. Each one came to share something about their corner of the world: big tech, politics, AI, local journalism, the U.S. election, happiness, trust, weapon systems, mediation and so on. Add to that four different university courses totaling 40 ECTS. I’ve experienced pure joy, cognitive dissonance, frustration, enthusiasm, gratitude — and everything in between. Now I just need to sit and stare out the window for a bit and see how it all settles in the coming months.

References:

https://tidsskrift.dk/politica/article/view/130383/176134

Brems, Miriam Kroman. 2024. Alternative news use in a high-trust media and political context: The spread and use of alternative media and their democratic implications in the least likely case of Denmark. PhD dissertation, Aarhus University.

Are You Ready to Watch Your Own Caricature Take Shape in Slow Motion Over Ten Months?

“Well, we’d better take Marie’s question now if we’re going to have time, because they tend to require slightly longer answers.”

We were 8.5 months into the fellowship, and nothing could surprise us anymore. Because yes, I was going to ask a question about what our guest thought was the one thing that makes humans human. And yes, I had asked big questions like that 50 times before. Just like Tanja would always ask about systemic change, Jamilla would offer a long and charming prelude to a question about bias, and Ida would say, “What do you base that on?”

Among a million other things, being a fellow at the Constructive Institute is about discovering, nurturing, and taming your pet topics—and witnessing a dozen other people doing the same.

You spend more than 500 hours in a room with other journalists, where you’re constantly being fed input about the state of the world, the role of journalism, artificial intelligence, new research, democracy, climate, data and algorithms, and experiences from real life in newsrooms—just to mention a fraction. And then you’re asked: So, what do you think about it all? I still can’t decide whether it’s healthy or unhealthy to spend that much time reflecting on the state of things.

But one thing is certain: it reveals the ontological lenses through which you view the world.

Because a pattern begins to emerge. And the unique thing about being part of this fellowship community is that you’re given the time and space to borrow each other’s lenses. I’ve had the privilege of seeing the world through Stockholm’s storytelling, through Eva’s empathetic curiosity, and I’ve been burdened by Tanja’s immense knowledge of climate and the environment. Thank you for the loan.

One thing is professional crusades; another is social dynamics and personality traits.

Because spending 10 months in a sheltered workshop with a group of kind, brilliant, sharp, reflective, and funny peers to discuss journalism and the state of the world is like a developing fluid for all your habits and character traits. It really ought to be secretly filmed for a reality show—a kind of professional Big Brother, where group dynamics are explored, alliances are built, and no one outside the walls quite understands how you feel.

This year, I’ve been confronted with my good and bad sides in a way I’ve never experienced before as an adult. I’ll spare readers of this essay the details of my newfound self-awareness, but suffice it to say you need to be ready to discover such things if becoming a fellow.

It is actually rather mindfucking to spend so much time analyzing everything around you and in you. Lately, I uttered the words, “I cannot stand the sound of my own voice anymore!” Needless to say, a couple of hours later I was, of course, back at pretending to be an expert on something. It’s like trying to hold back a tidal wave with a rake, and apparently, that’s me.

It has been a bit like being trapped in Tivoli’s hall of mirrors. We have seen ourselves and each other from all flattering and unflattering angles, which is why we can now practically finish each other’s sentences. It has been a pleasure and a privilege, and I wouldn’t trade this community for anything.

Just like another, more famous fellowship that cemented their bond with the pledges, “You have my sword,” “And my bow,” “And my axe,” I will look back on this fellowship as a community that challenged constructive journalism critically with the pledges, “You have my existential wonder!”, “And my systemic critique!”, “And my bias awareness!” May all fellows from now on experience the same frustrating and wonderful predictability.