How To Not Stigmatize When Doing Journalism on Minorities

“How can journalists describe problems in minority neighborhoods, without adding to stigmatizing and thereby further polarizing society?”

Mathilde Graversen, former Constructive Institute Fellow and journalist at the Danish newpaper Berlingske

Mathilde Graversen applied for a fellowship at Constructive Institute so she could look into why some people in minority neighborhoods feel like being in opposition to the surrounding society, what role the media plays, and how to do journalism on ethnic minorities and minority neighborhoods without adding to stigmatization. Through a two episode podcast she instead created a space for a democratic and constructive dialogue.

How She Did It

As a journalist at the danish newspaper Berlingske Mathilde Graversen has been covering terrorist attacks, gang crime and most recently migration and integration. She has been disturbed over some of the serious challenges we face as a society in the area of integration, and at the same time deeply disturbed over the polarization, when it comes to talking about and handling these challenges.

Over the ten months fellowship Mathilde boiled her worries down to two podcast episodes where she gives the microphone to people representing minorities, who she would normally interview. The podcasts are in danish, since the sources are danes. But go and read the key takeaways in the end of this text.

“The biggest takeaway for me has been how our fundamental way of understanding and communicating the world in categories seems to play a crucial role.”

How She Did the Podcast

Mathilde made the podcast as an experiment, and in two episodes she takes you through some of the interviews, courses at university and thoughts she had during her fellowship.

“I have called the podcast “Når dem vi taler om, ser på os” meaning “when the people we talk about, look at us” with reference to the essential issue with categories such as “us” versus “them”, majority versus minority, journalists versus sources,” Mathilde explains.

Mathilde Graversen on her way to hand over the microphone to people she would usually interview and portray. Photo: Maria Albrechtsen Mortensen

In the podcast she lets some of the people she would normally interview and portray, hold the microphone to give their view on her and other journalists. And she comments on their inputs.

“In stead of sitting alone in the podcast studio interpreting on my own – me being part of the ethnic majority not living in a minority neighborhood – I invited Saleh Zormati to join me,” says Mathilde.

22-year old Saleh Zormati is a young man from a minority neighborhood now studying, voluntering to break down prejudices and keeping up with news. His family still lives in the neighborhood Gellerup listet by the Danish government as a “hard ghetto” . He shares his thoughts throughout the podcast from his point of view.

The first episode of the podcast is about main reasons for feeling in opposition to the surrounding society.

“This feeling is sometimes described as “modborgerskab” roughly translated to “counter-citizenship”, which is seen especially amongst some young men in minority neighborhoods. And a feeling sometimes being realized by criminal behaviour,” Mathilde explains.

Mathilde has talked to residents in minority neighborhoods, researchers, social workers, a former criminal, young students, teachers, police etc. about why this feeling occurs, and some of the things they mention again and again are: A bad school experience, social problems at home, a different upbringing where boys meet few limits, a lack of trust in grown-ups, new laws being seen as discriminating, and ethnic minorities’ low representation in news media in generel.

The second podcast episode is about the media. How journalism on minorities and minority neighborhoods is done today, and how it can improve. In this episode residents critique journalists for letting one or a few people’s criminal activities lead to the stigmatization of a whole group of people.

“This is a critique that spurs us to a look at how we divide ourselves into groups of people – sometimes based on ethnicity, which again requires a look at the term “ethnicity”,” Mathilde proposes.

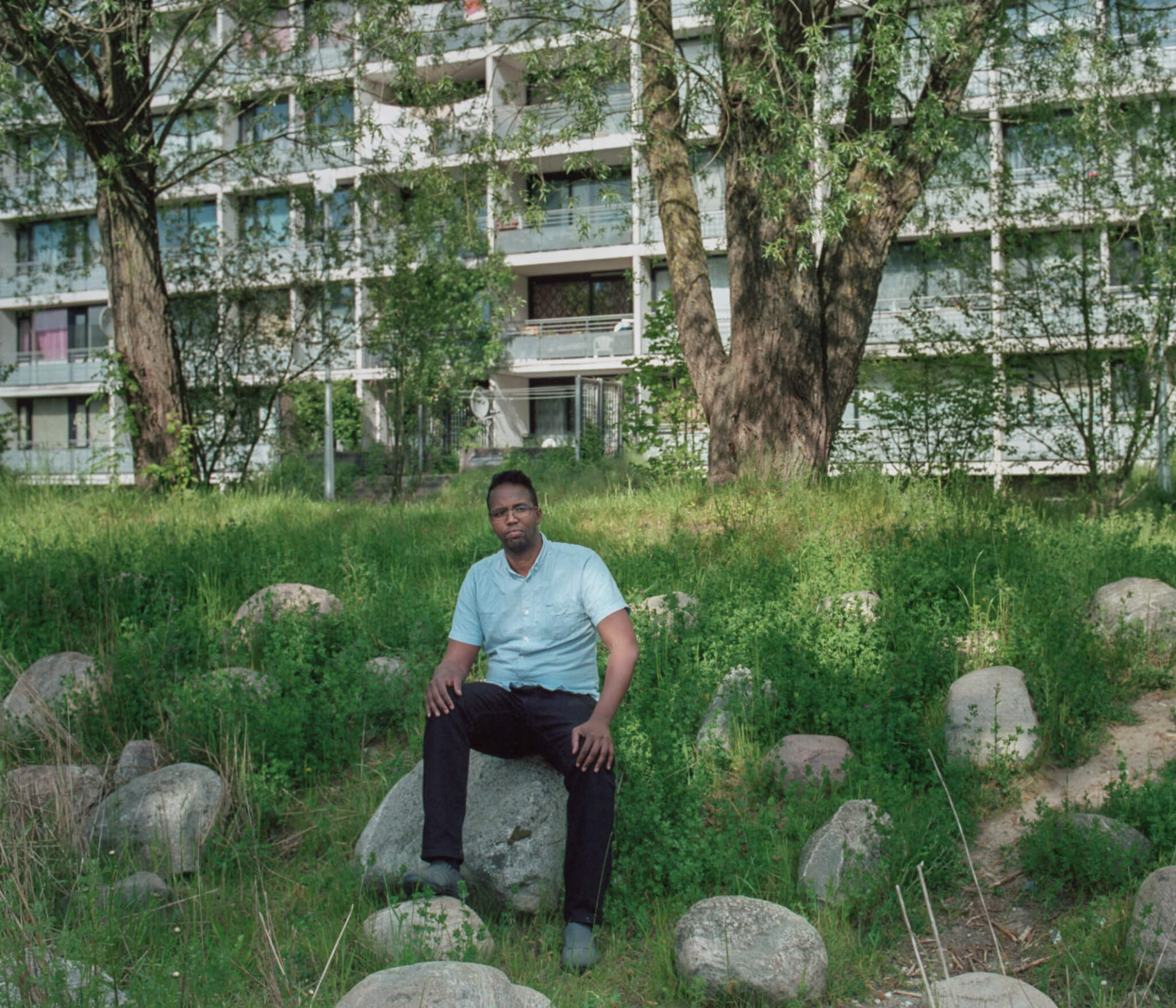

Saleh Zormati, a 22-year-old man from a minority neighborhood, criticizes how journalism on minorities is done. Photo: Maria Albrechtsen Mortensen

“When we as journalists describe problems in our society – in order for us all to handle these problems – we try to describe reality,” Mathilde explains.

When doing so, journalist tap into the categories that the majority uses to understand the world around them and to communicate.

“With categories, I mean: I don’t have to describe the many leafs, the bark and the roots – I can just use the category “tree”. Or the categories “migrant”, “refugee”, “muslim” or “dane”. Our minds put things into boxes or categories, so we can make sence of the world. But with categories comes generalizations, and sometimes people don’t see themselves as part of the category, they are placed in when described in media,” Mathilde elaborates.

“We cannot avoid categories as journalists, but we can make an effort to use the right ones at the right time, and we can add nuance and perspective in order to both describe problems, but at the same time give an overall fair presentation of reality,” Mathilde concludes.

At Gellerupparken, close to Aarhus in Denmark, residents are criticizing journalists for stigmatizing an entire neighborhood based on the actions of a few residents. Photo: Maria Albrechtsen Mortensen

Key Takeaways

1. Use the right category at the right time. Be as precise as possible and be thoughtful of the terms you use to describe people. Be critical towards categories presented by politicians and authorities. And challenge your own habits on this area.

2. Correlation does not imply causation. Be aware that correlation does not imply causation — and that causation is easily linked in our heads, when we hear about a problem and “them.” Mention what is known about the cause of a problem and what is not.

3. Add nuance and perspective. When describing a problem, remember to also describe the whole picture with nuance and perspective. Crime for instance is a problem in some minority neighborhoods worth looking into, but do also mention how crime in general has fallen the last years in these areas.

4. Involve minorities. Talk with more people with a minority background — not only when the story is about crime and unemployment, but also when it is about everyday life. Ethnic minorities are underrepresented as sources in news media in Denmark.

5. Look for mainstream, not extreme. Don’t always go for the most extreme views held by few people, but add voices from the middle of the Bell Curve where most people find themselves.

6. Remember solutions and progress. After describing a problem, follow through and describe what could be done to solve it, what is being done and how it is going.